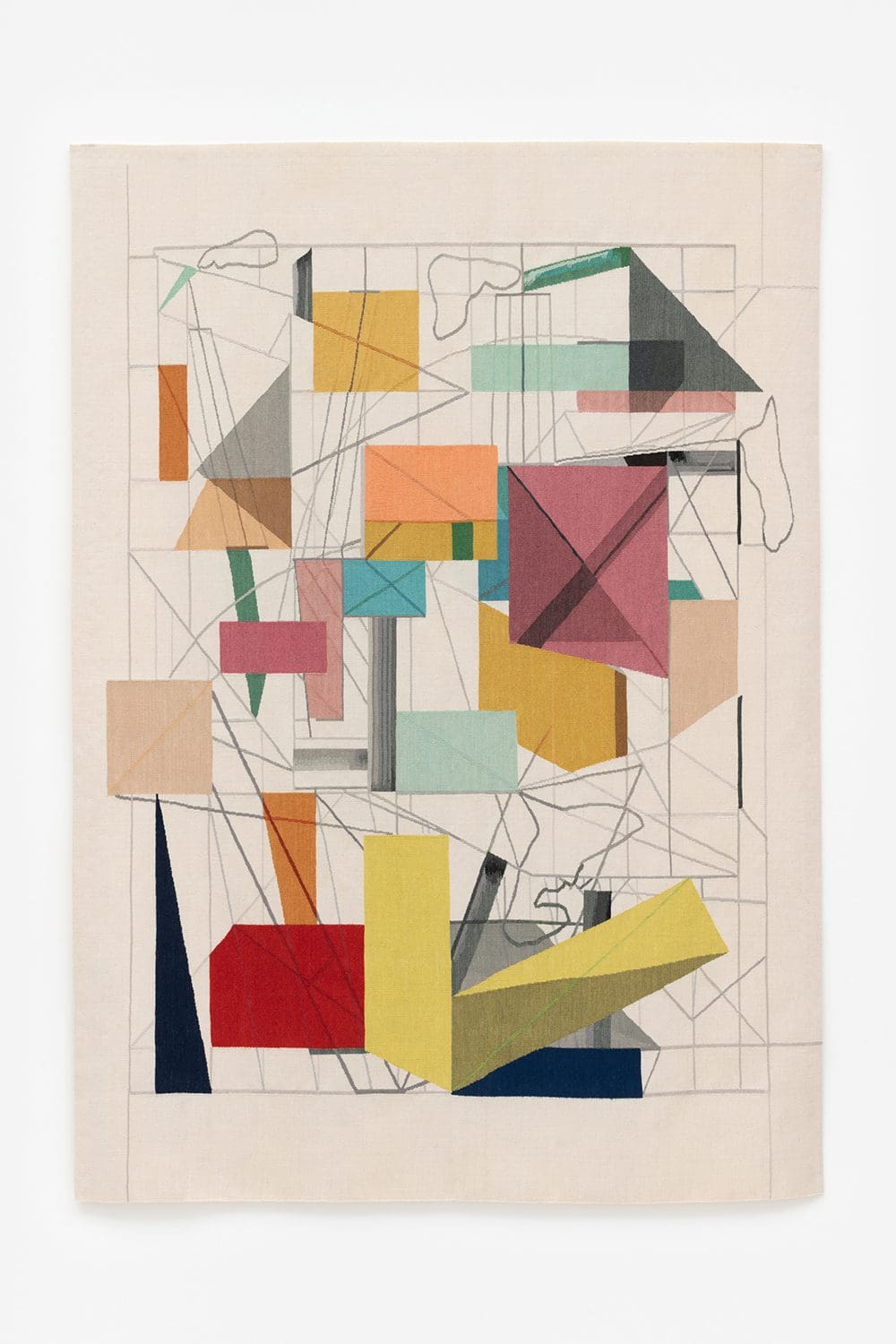

We are proud to present “Compendium Tree” by British Artist, Andrew Bick, developed together with Hales Gallery, London.

Woven in New Zealand wool and silk, the aubusson style tapestry represents Bick’s first foray into the medium with outstanding results that mark an evolutionary moment in his exploration of textiles.

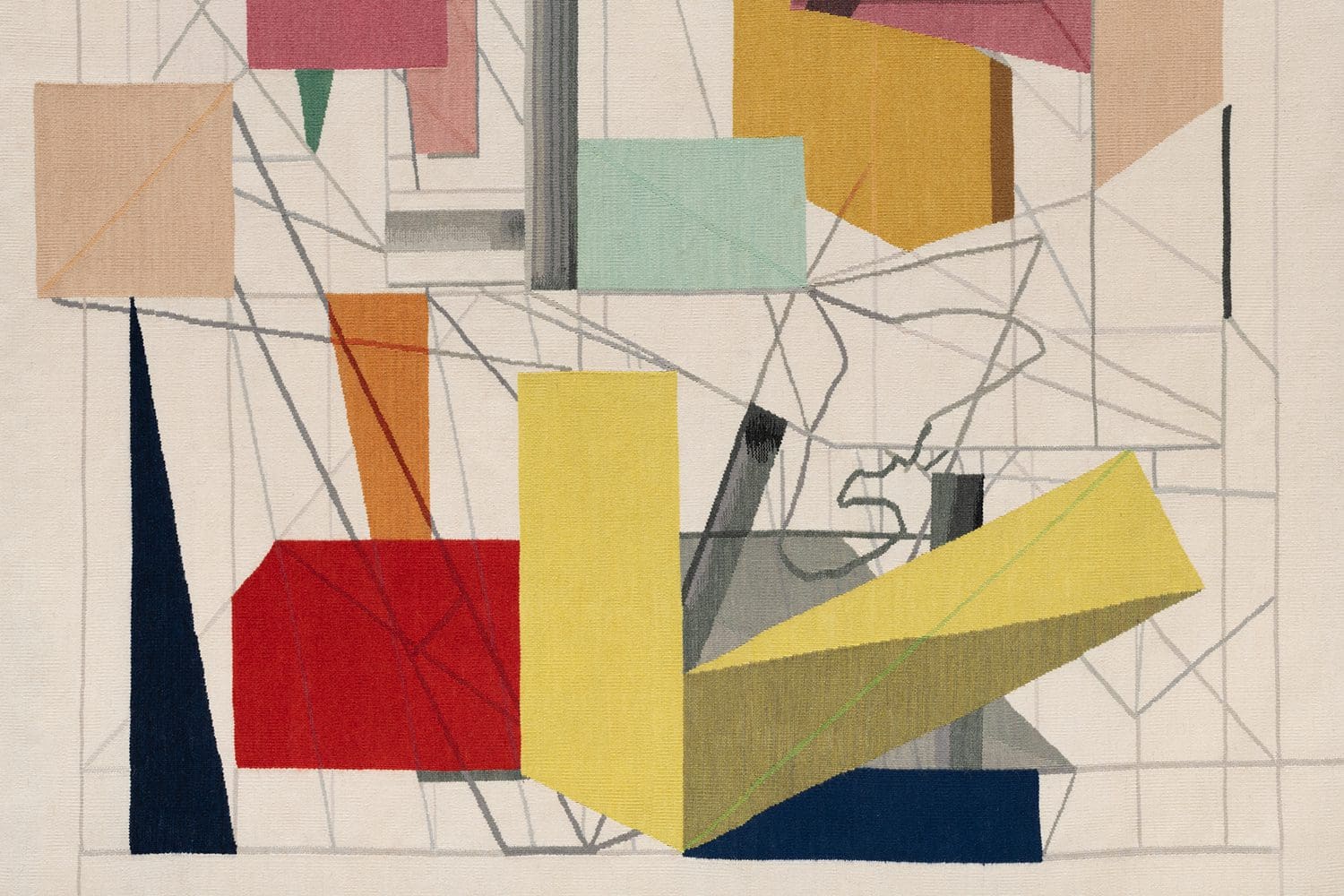

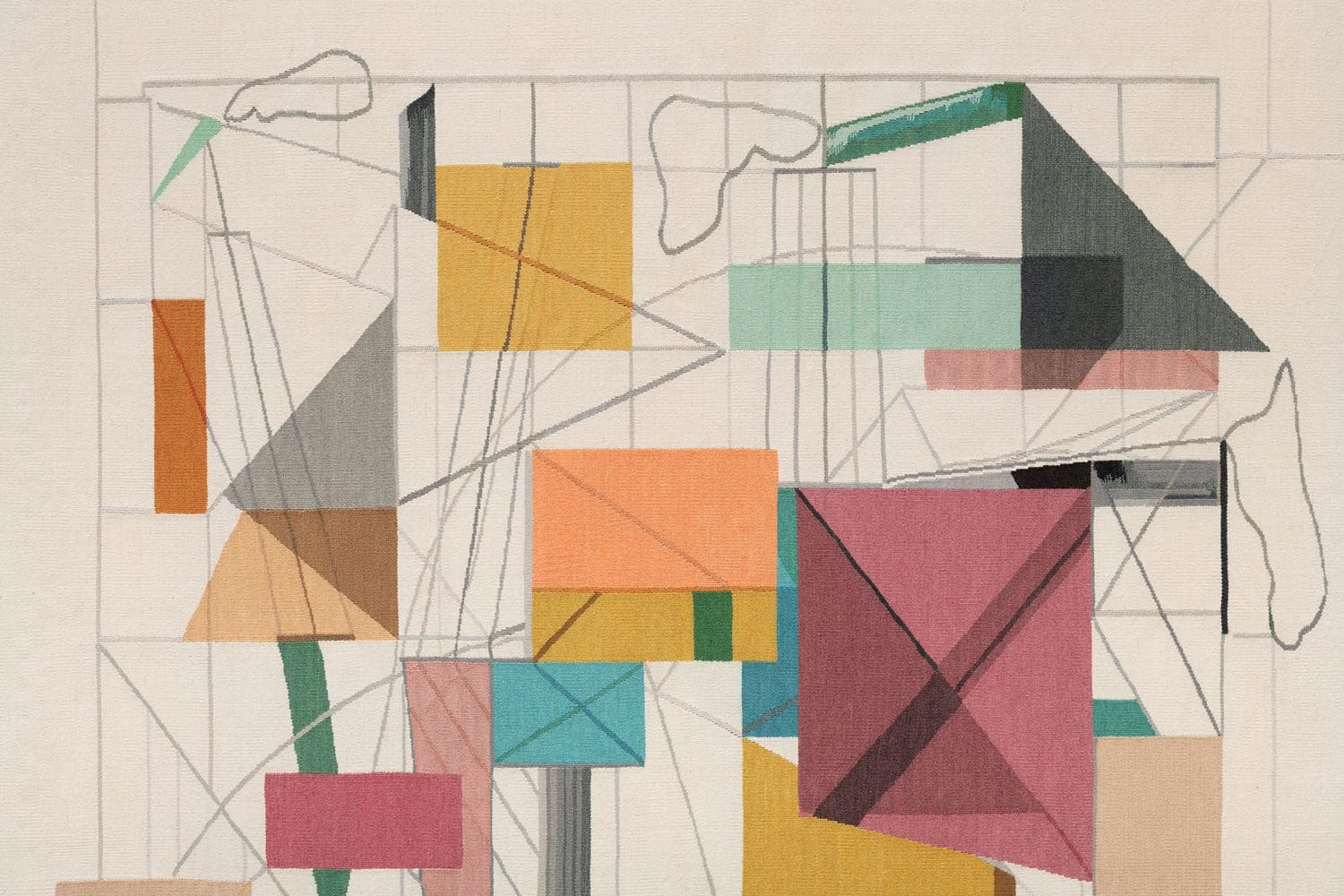

“Compendium Tree” was created using two motifs: a grid sequence and an image. The grid sequence is a system of numerical count-up in odd numbers, which was used by Paul Klee to form a basic geometrical model for drawing a tree. The second motif is Fibonacci numbers, which determine the width and length of lines and blocks of color. The two structures are superimposed on a grid diagram and then collaged with sections of the same paper to create a shifting sense of build-up and visual collision.

“I classify the different aspects of my work, and the cartoon drawing for this tapestry falls into the category of ‘compendium.” These are works in which is where several different methods and motifs are piled together, creating a mesh of such complexity that, in both making the drawing and looking at it, a process of visual untangling becomes a key element.” – Andrew Bick.

Odabashian’s weavers worked from a high-resolution digital photograph and custom dyed threads, to develop this highly detailed tapestry over the course of six months.

“The end result is a tapestry that memory of drawing embedded in any physical structure, and to a sense of light floating across space.” – Andrew Bick.

We spoke to Andrew Bick at his studio in London to learn more about the piece:

Can you share with us how this collaboration with Odabashian came about?

Andrew Bick: I met Jaime Odabachian in May of 2019. A few months later, he visited my studio and we had a conversation about his work, which ultimately led to the collaboration.

During the pandemic, we continued to work slowly, with me sending video clips of my drawings to Jaime and Paul Hedge (Hales Gallery). I began by thinking about how this drawing might be transposed into a tapestry, for which I would be sending an image as an ‘instruction’ and would have no control over the weaver’s interpretive processes. The sequence of drawing experiments, and there were six attempts before arriving at the final version, became a crucial aspect of the development, rather than stages towards a fixed arrival point.

As such, the drawings are proposing ways in which not just the interpretation of the idea of ‘tree’ might need to be guessed at or improvised but also a collision of two, probably incompatible artists, from different eras, Paul Klee (1879-1940) and Gillian Wise (1936-2020).

Part of the thinking here is that meaning always remains out of reach and out of control and my obsession with looking, adjusting, shifting, and correcting the work benefits greatly from the need to hand over management of ‘the problem’ of making a work to a team of skilled weavers. The buried aspects of the quotation, from Paul Klee and, over a much longer period in my own work, the grid usage of British artists Gillian Wise, thus got taken on a much stranger journey than I could imagine for myself.

What made you choose that particular design over the other explorations?

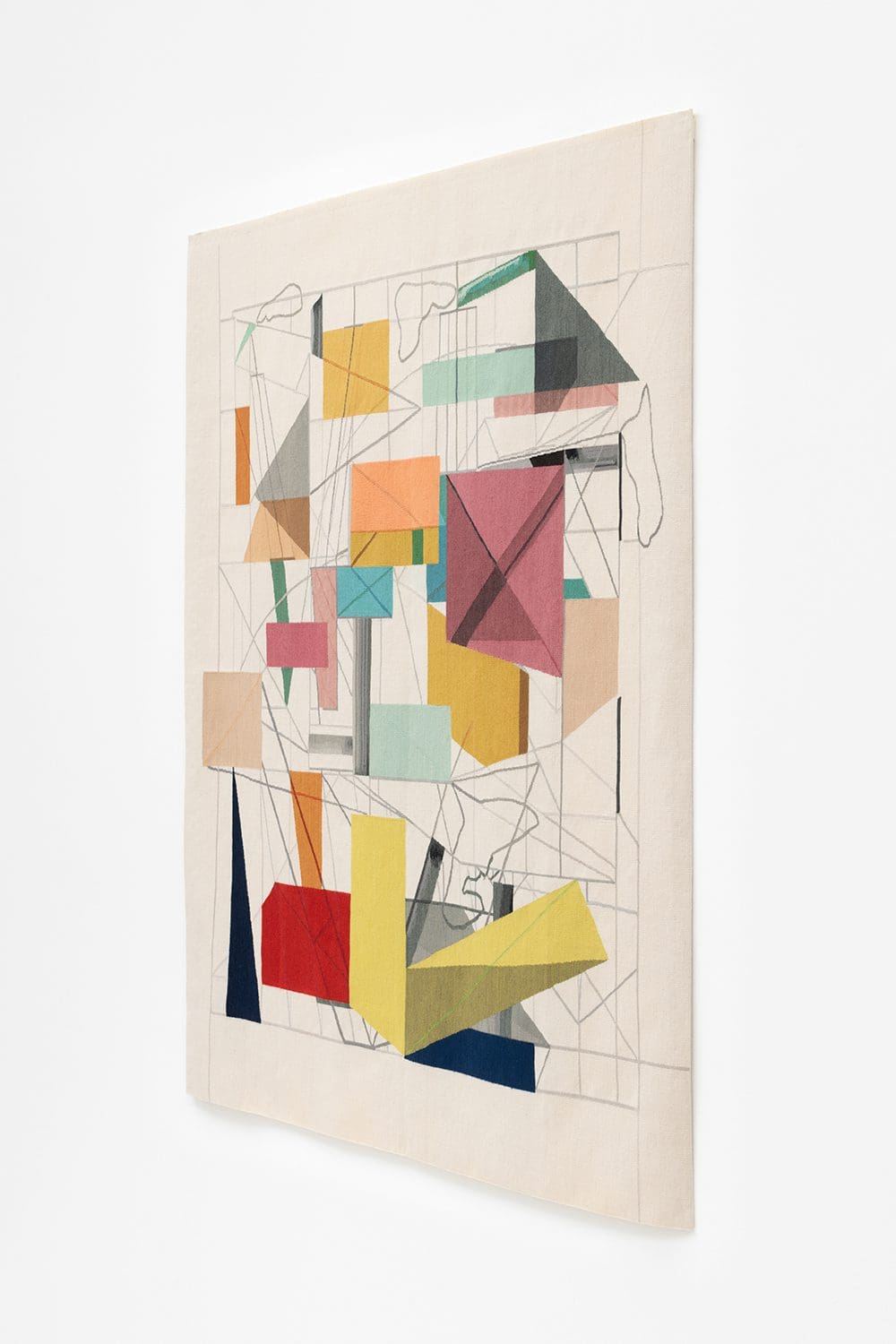

AB: It seemed to offer the most potential to be reworked in this new for me / ancient medium. The process of transcribing the piece into a tapestry created something that was far more spatially dynamic than the original drawing. This gave the piece the quality of a “mobile” it was as if you are looking at things hanging in space, and they have the capacity to move slightly.

Because the drawing was to be transposed into a tapestry, additional material complexities were added as means to generate surprise through processes I could not edit or interfere with. I was thinking about how a visual equivalence to translation might become embodied in a hand dyed and woven piece. A key aspect was that the addition of collaged elements using 640gsm paper adds a relief layer of approximately 1.5mm. This creates shadows, which interact with the pencil lines of various widths and densities as another subtle gradation of line.

Can you describe how this original drawing was then translated into the tapestry?

AB: The weavers worked from a high-resolution digital photograph and colour swatches. This process involved forms of reinvention germane to weaving only, such as the recreation of an ultra-fine pencil line through a shift in the weaving pattern over a wider band. How and why this visually recreates the fine line I have no idea, but it does.

Elsewhere a particular grain and texture of watercolour has been mimicked by adding a small amount of sparkly fabric to the weave. Again, it works brilliantly, and there is no way, outside the skill of weaving, to know why this works optically. Ultimately, this tapestry has an address to the architectural, to an idea of the memory of drawing embedded in any physical structure, and to a sense of light floating across space.

What were some of the most notable learning curves that you enjoyed along the way?

AB: Two really, one was because I wanted to push the envelope, even though I haven’t done it before, I wanted to find out how far the medium of tapestry could go; and the other was going with Paul to meet Zenzie Tinker, a textiles conservator, who is an expert on tapestry, to learn more about the medium and its skills, realizing that we were making something very contemporary but with this very old medium. I now have a strong desire to do more work with tapestry, and if we had the chance to scale things up, that would be fantastic.

How did you feel when you saw the final tapestry for the first time?

AB: I was surprised and mesmerised by how it seemed to float. As I mentioned earlier, the elements in the design seem to suspend and shimmer in the air giving it a quality that I didn’t really expect.

How did Odabashian’s experience with tapestry making help to guide you through the process?

AB: My conversations with Jaime about the traditions of tapestry making but also its relationship with modernism were a good starting point. The previous projects they have done with great artists also gave me a lot of confidence. The process of collaborating was very smooth Jaime was very committed to the project but also gave me total freedom to experiment and explore ideas. The quality of the samples I received during the process also confirmed we were going to make something special.

How does this rug fit into your work in terms of the pieces that came before it and what you have been working on since?

AB: Around 2021, I started sewing together sections of linen canvas and stretching them as opposed to using a single sheet of linen in a painting, so I started to think about seams and edges and how fabric stretches and folds.

This transformation is ongoing and I think once I’ve had more time with this piece of work and once hopefully we’ve had the opportunity to upscale to do another one, it’s going to transform a lot more in my work. I think it’s a brilliant way to fuse time together, something that was devised centuries ago and to deal with it in a very contemporary way, but to do so slowly with the precision of the materials.